A Radiographic Abnormal Anomalous Anomaly: Iatrogenic Cervicofacial/Retropharyngeal Subcutaneous Emphysema:

|

|

However, such awareness should not imply that the technician or dental assistant is expected, should feel obligated, or is legally bound to provide a specific radiographic interpretation or diagnosis of these entities. Rather, it conveys the idea that atypical/abnormal/anomalous radiographic findings observed by the technician and/or dental assistant require further evaluation by the patient's dentist and/or physician and respective consultants indicated by these care providers. Generally, this process is well understood and occurs daily in imaging facilities and dental practices.

Nevertheless, as the radiology or dental assistant gains practical experience by viewing numerous radiographic images, they will naturally develop a "radiographic pattern recognition" mental library that will aid them in distinguishing normal from atypical radiographic findings. In this regard, these members of the health care team become capable of categorizing more commonly observed abnormal patterns seen in radiographic image surveys from those that are rare, bizarre, and rarely detected.

What constitutes a bizarre finding? According to the authors the definition of a bizarre radiographic pattern would be one that requires the observer to search the radiographic scientific literature or consult with a diagnostic radiology specialist for interpretive answers. Thus, when the radiographic technician or dental assistant is challenged by the observation of an uncommon radiographic pattern they need to access their "radiographic pattern recognition" mental library for potential anomalies. By employing this process they can reach a more comfortable level of abnormal radiographic pattern recognition so that even bizarre configurations can be detected and referred for further interpretation.

Report of a Case Involving an Anomalous Radiographic Pattern

Case reports are common in the healthcare scientific literature. They often provide a means of disseminating clinical and radiographic information concerning rare and unusual anomalies/abnormalities to practitioners. Such information permits the healthcare provider to remain updated on the incidence of these lesions and current approaches to their treatment and management. Historically, case reports in the dental diagnostic radiology literature presented cases involving unusual "bizarre" findings. These were termed "Radiographic Oddities" in the Journal of Dental Radiography and Photography series published by the Eastman Kodak Company in the last century.2 As is common in the practice of oral radiology and pathology, this case was received with an incomplete clinical history and limited follow-up information. Therefore, it was challenging if not impossible to render a definitive diagnosis. However, it is the authors' opinion that the uniqueness of this patient's radiographic presentation was sufficient to suggest the condition described herein and to consider inclusion of this unusual entity in ones "radiographic pattern recognition" mental library.

Clinical History

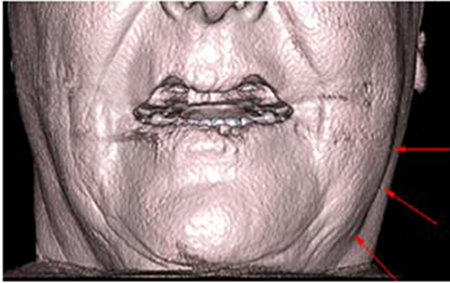

A middle aged white female patient presented to an imaging facility for a CBCT image examination prior to dental treatment which was to include placement of maxillary dental implants. No unusual health history was reported to the imaging technician. However, the technician reportedly observed the patient holding her symptomatic left cheek; which was swollen along the mandible from its left angle to the region of the left mandibular canine (tooth #22) (Figure 1). Subsequent verbal history obtained from the referral source disclosed that the patient had received endodontic therapy on the left mandibular first premolar tooth (#21) the morning of the CBCT imaging examination. Although the patient was experiencing some discomfort this did not preclude her from completing the CBCT image examination appointment.

Nevertheless, as the radiology or dental assistant gains practical experience by viewing numerous radiographic images, they will naturally develop a "radiographic pattern recognition" mental library that will aid them in distinguishing normal from atypical radiographic findings. In this regard, these members of the health care team become capable of categorizing more commonly observed abnormal patterns seen in radiographic image surveys from those that are rare, bizarre, and rarely detected.

What constitutes a bizarre finding? According to the authors the definition of a bizarre radiographic pattern would be one that requires the observer to search the radiographic scientific literature or consult with a diagnostic radiology specialist for interpretive answers. Thus, when the radiographic technician or dental assistant is challenged by the observation of an uncommon radiographic pattern they need to access their "radiographic pattern recognition" mental library for potential anomalies. By employing this process they can reach a more comfortable level of abnormal radiographic pattern recognition so that even bizarre configurations can be detected and referred for further interpretation.

Report of a Case Involving an Anomalous Radiographic Pattern

Case reports are common in the healthcare scientific literature. They often provide a means of disseminating clinical and radiographic information concerning rare and unusual anomalies/abnormalities to practitioners. Such information permits the healthcare provider to remain updated on the incidence of these lesions and current approaches to their treatment and management. Historically, case reports in the dental diagnostic radiology literature presented cases involving unusual "bizarre" findings. These were termed "Radiographic Oddities" in the Journal of Dental Radiography and Photography series published by the Eastman Kodak Company in the last century.2 As is common in the practice of oral radiology and pathology, this case was received with an incomplete clinical history and limited follow-up information. Therefore, it was challenging if not impossible to render a definitive diagnosis. However, it is the authors' opinion that the uniqueness of this patient's radiographic presentation was sufficient to suggest the condition described herein and to consider inclusion of this unusual entity in ones "radiographic pattern recognition" mental library.

Clinical History

A middle aged white female patient presented to an imaging facility for a CBCT image examination prior to dental treatment which was to include placement of maxillary dental implants. No unusual health history was reported to the imaging technician. However, the technician reportedly observed the patient holding her symptomatic left cheek; which was swollen along the mandible from its left angle to the region of the left mandibular canine (tooth #22) (Figure 1). Subsequent verbal history obtained from the referral source disclosed that the patient had received endodontic therapy on the left mandibular first premolar tooth (#21) the morning of the CBCT imaging examination. Although the patient was experiencing some discomfort this did not preclude her from completing the CBCT image examination appointment.

Incidental Radiographic CBCAT Findings

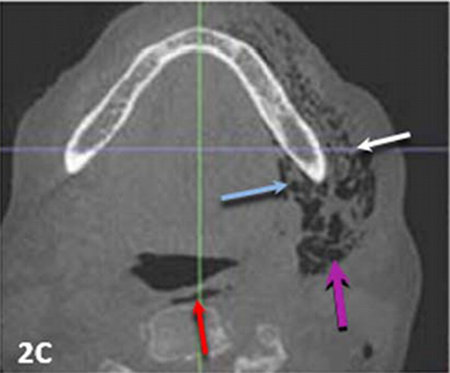

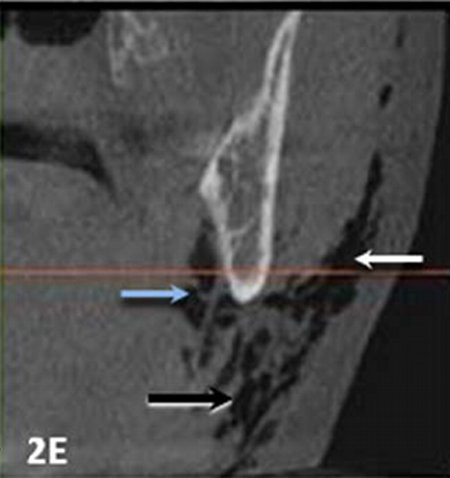

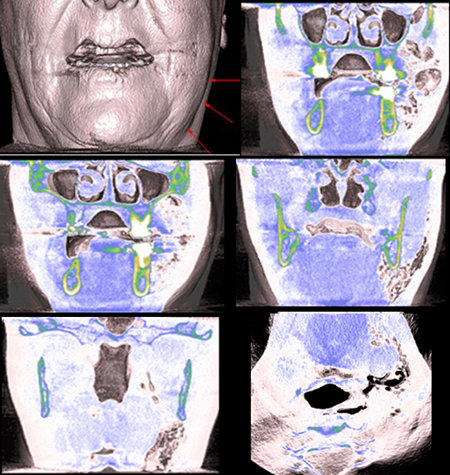

CBCT images made from this appointment exhibited numerous incidentally observed round to irregular hypodense areas with defined margins. These were unilaterally located in the patient's soft tissues adjacent to the lateral, medial and inferior borders of the body of the left mandible (Figure 2, A-E composite views). In the axial views, the radiographic pattern created by these anomalous areas was suggestive of one that mimicked the appearance of an "expanded, lace tablecloth." These radiographic findings are consistent with the radiographic presentation of cervicofacial/retropharyngeal subcutaneous emphysema.3-6

Incidental Clinical Photographic and Radiographic Findings

Development of an interpretative radiographic hypothesis concerning the pathogenesis of cervicofacial/retropharyngeal subcutaneous emphysema requires collection of information from the patient's medical and dental history, clinical photo graphs, and reconstructed transaxial CBCT image views. Clinical and radiographic correlation is the key to establishing a definitive diagnosis.

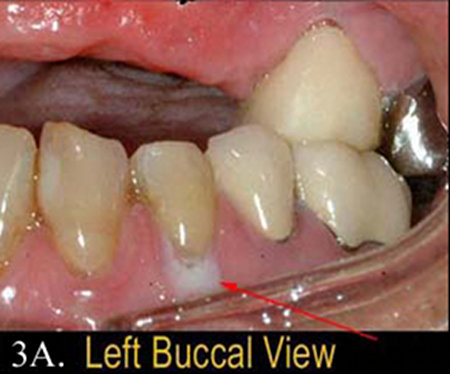

In this case the clinical photograph of tooth #21 shows a focal, crescent shaped, "milky" white, opaque area over the buccal gingival surface below the level of the cemento-enamel junction of tooth #21 (Figure 3A). No other teeth in this area display a buccal gingival pattern associated with a similar appearance.

CBCT images made from this appointment exhibited numerous incidentally observed round to irregular hypodense areas with defined margins. These were unilaterally located in the patient's soft tissues adjacent to the lateral, medial and inferior borders of the body of the left mandible (Figure 2, A-E composite views). In the axial views, the radiographic pattern created by these anomalous areas was suggestive of one that mimicked the appearance of an "expanded, lace tablecloth." These radiographic findings are consistent with the radiographic presentation of cervicofacial/retropharyngeal subcutaneous emphysema.3-6

Incidental Clinical Photographic and Radiographic Findings

Development of an interpretative radiographic hypothesis concerning the pathogenesis of cervicofacial/retropharyngeal subcutaneous emphysema requires collection of information from the patient's medical and dental history, clinical photo graphs, and reconstructed transaxial CBCT image views. Clinical and radiographic correlation is the key to establishing a definitive diagnosis.

In this case the clinical photograph of tooth #21 shows a focal, crescent shaped, "milky" white, opaque area over the buccal gingival surface below the level of the cemento-enamel junction of tooth #21 (Figure 3A). No other teeth in this area display a buccal gingival pattern associated with a similar appearance.

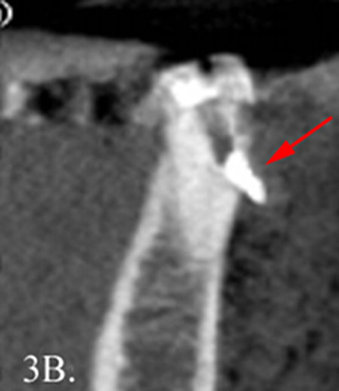

Corresponding to the clinically opaque buccal gingival lesion related to tooth #21 is a CBCT transaxial arch radiographic view of tooth #21. This image exhibits a radiolucent defect on the occlusal surface of tooth #21 and a pulpal hyperdensity consistent with a metallic root canal filling material. In the transaxial view, this material appears to be extruded beyond the buccal root surface and into the adjacent buccal soft tissue region (Figure 3B). While focusing on tooth #21, the observer of the radiographs in this case should not neglect the hypodense areas associated with the apices of the mesial and distal roots of molar tooth #19. These patterns are suggestive of persistent apical inflammation or fibrous filling defects (apical scars). It is the opinion of the authors that despite the radiographic patterns associated with #19, the significant pathology in this case is most likely related to treatment outcomes associated with tooth #21.

These clinical and radiographic findings are suggestive of an iatrogenic etiology where root perforation or a possible vertical root fracture occurred during the endodontic procedure. Disinfection of the root canals during endodontic therapy is often accomplished by irrigation with hydrogen peroxide or similar cleansing agent solution. Because of the perforation or root fracture the cleansing agent solution theoretically could have had the opportunity to leak past the root surface into adjacent alveolar bone and associated gingival soft tissue. The consequences of this material's effect on these tissues could have caused the blanching and bleaching of the gingiva or alternatively, a mild chemical burn, resulting in the "milky" white, opaque area over the buccal gingival surface adjacent to the cervical region of the tooth.

Additionally, if an air syringe or air driven handpiece was used during the endodontic preparation and treatment of this tooth, a pathway could have been created for air and/or the cleansing solution to disperse further into adjacent soft tissue fascial planes. This could account for the source of the problem which resulted in the creation of the radiographic areas suggestive of cervicofacial/retropharyngeal subcutaneous emphysema.

Additionally, if an air syringe or air driven handpiece was used during the endodontic preparation and treatment of this tooth, a pathway could have been created for air and/or the cleansing solution to disperse further into adjacent soft tissue fascial planes. This could account for the source of the problem which resulted in the creation of the radiographic areas suggestive of cervicofacial/retropharyngeal subcutaneous emphysema.

Anatomical Description

The fascial spaces involved in this case were radiographically and anatomically interpreted to include the mentalis, masticator, buccal, parotid, submandibular, parapharyngeal, and contiguous retropharyngeal spaces. Located within the masticator space are the superficial temporal, deep temporal, pterygomandibular, and masseteric spaces in addition to the major muscles of mastication. These muscles include the lateral and medial pterygoids, temporalis and masseter muscles. The major nerves supplying the mandibular aspects of the oral cavity and surrounding structures including the inferior alveolar, lingual, chorda tympani and long buccal nerves are also found within the masticator space. The retropharyngeal space is contiguous with the mediastinal space and this relationship could theoretically permit air to dissect into this critical area as well. In this case air was apparently confined to the fascial spaces previously described.

It is likely that air would initially spread to the regions that directly abut the mandibular molars and premolars. These regions include the buccal, submandibular, sublingual, pterygomandibular, masseteric and parotid spaces. From the pterygomandibular and submandibular spaces air could spread to the parapharyngeal space and thereby to the retropharyngeal space. Lastly, air from the masseteric and pterygomandibular space would spread to the superficial and deep temporal spaces.

Of note is the fact that neither the oral and maxillofacial surgery textbook edited by Hupp et al. nor the anatomy textbook edited by Liebgott, list the parotid space among those to which infections of the dentition will spread.7-8The extremely thick investing fascia that surrounds the parotid gland is probably the reason for the segregation of the infection from the parotid space. Thus, in this clinical case of subcutaneous emphysema, the almost immediate spread of air into the parotid space is of significance.

Discussion

When considering the respiratory system the term emphysema refers to a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in which the lung tissues surrounding the terminal air sacs (alveoli) are destroyed. Retention of entrapped air in the alveoli of the lung is most commonly caused by tobacco smoking and extended exposure to air pollution. Clinically, this results in an inability to exhale and shortness of breath.

Conversely, subcutaneous emphysema is the presence of air or gas in the interstitial spaces of the connective tissues below the skin. It is caused by entrapment of air or gas which has entered the connective tissues and dissects along the fascial planes to create spaces and cavitational defects. This process can be initiated by the spread of infection associated with necrosis or acute cellulitis. Additionally, it may arise from air forced into tissue from a traumatic event such as accidental penetration, blunt injury or trauma of iatrogenic origin.

A variety of medical and dental procedures have been implicated in the development of iatrogenic subcutaneous emphysema. In the practice of dentistry, any procedure that utilizes a high speed air-driven handpiece instruments in conjunction with pressurized air-water coolants - such as restorative procedures, tooth exextractions, endodontic treatment, and periodontal surgeries3-6 - harbors the potential to introduce air into the soft tissues. Interestingly, Hulsmann and Hahn9 documented a case of subcutaneous emphysema related to use of hydrogen peroxide and sodium hypochlorite as cleansing agents during endodontic therapy.

The classic presenting symptom of subcutaneous emphysema is abrupt onset enlargement of the soft tissues, which is typically observable within the first hour of the inciting event. Exploration of the involved site may also reveal crepitus, a sensation of grating, crackling or popping on palpation. Despite its dramatic presentation, patients who develop iatrogenic subcutaneous emphysema generally do well and show complete resolution of their symptoms within 2 to 5 days. Broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy may be considered to prevent secondary infection. On occasion, more significant complications such as respiratory distress may arise due to spread of the air to the mediastinum (pneumomediastinum).10 Although subcutaneous emphysema involving the cervicofacial/ retropharyngeal region is not routinely fatal there have been rare reports of death associated with this condition.11

Conclusions

An incidental bizarre, abnormal, anomalous radiographic pattern has been described to help radiology technicians and dental assistant personnel broaden the inventory in their "radiographic pattern recognition" mental libraries. Providing this group of healthcare personnel with an understanding of the terminology, etiology, clinical findings, and prognosis associated with the unusual radiographic pattern observed in this case ensures that referral for further interpretation can be performed more proficiently.

The fascial spaces involved in this case were radiographically and anatomically interpreted to include the mentalis, masticator, buccal, parotid, submandibular, parapharyngeal, and contiguous retropharyngeal spaces. Located within the masticator space are the superficial temporal, deep temporal, pterygomandibular, and masseteric spaces in addition to the major muscles of mastication. These muscles include the lateral and medial pterygoids, temporalis and masseter muscles. The major nerves supplying the mandibular aspects of the oral cavity and surrounding structures including the inferior alveolar, lingual, chorda tympani and long buccal nerves are also found within the masticator space. The retropharyngeal space is contiguous with the mediastinal space and this relationship could theoretically permit air to dissect into this critical area as well. In this case air was apparently confined to the fascial spaces previously described.

It is likely that air would initially spread to the regions that directly abut the mandibular molars and premolars. These regions include the buccal, submandibular, sublingual, pterygomandibular, masseteric and parotid spaces. From the pterygomandibular and submandibular spaces air could spread to the parapharyngeal space and thereby to the retropharyngeal space. Lastly, air from the masseteric and pterygomandibular space would spread to the superficial and deep temporal spaces.

Of note is the fact that neither the oral and maxillofacial surgery textbook edited by Hupp et al. nor the anatomy textbook edited by Liebgott, list the parotid space among those to which infections of the dentition will spread.7-8The extremely thick investing fascia that surrounds the parotid gland is probably the reason for the segregation of the infection from the parotid space. Thus, in this clinical case of subcutaneous emphysema, the almost immediate spread of air into the parotid space is of significance.

Discussion

When considering the respiratory system the term emphysema refers to a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in which the lung tissues surrounding the terminal air sacs (alveoli) are destroyed. Retention of entrapped air in the alveoli of the lung is most commonly caused by tobacco smoking and extended exposure to air pollution. Clinically, this results in an inability to exhale and shortness of breath.

Conversely, subcutaneous emphysema is the presence of air or gas in the interstitial spaces of the connective tissues below the skin. It is caused by entrapment of air or gas which has entered the connective tissues and dissects along the fascial planes to create spaces and cavitational defects. This process can be initiated by the spread of infection associated with necrosis or acute cellulitis. Additionally, it may arise from air forced into tissue from a traumatic event such as accidental penetration, blunt injury or trauma of iatrogenic origin.

A variety of medical and dental procedures have been implicated in the development of iatrogenic subcutaneous emphysema. In the practice of dentistry, any procedure that utilizes a high speed air-driven handpiece instruments in conjunction with pressurized air-water coolants - such as restorative procedures, tooth exextractions, endodontic treatment, and periodontal surgeries3-6 - harbors the potential to introduce air into the soft tissues. Interestingly, Hulsmann and Hahn9 documented a case of subcutaneous emphysema related to use of hydrogen peroxide and sodium hypochlorite as cleansing agents during endodontic therapy.

The classic presenting symptom of subcutaneous emphysema is abrupt onset enlargement of the soft tissues, which is typically observable within the first hour of the inciting event. Exploration of the involved site may also reveal crepitus, a sensation of grating, crackling or popping on palpation. Despite its dramatic presentation, patients who develop iatrogenic subcutaneous emphysema generally do well and show complete resolution of their symptoms within 2 to 5 days. Broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy may be considered to prevent secondary infection. On occasion, more significant complications such as respiratory distress may arise due to spread of the air to the mediastinum (pneumomediastinum).10 Although subcutaneous emphysema involving the cervicofacial/ retropharyngeal region is not routinely fatal there have been rare reports of death associated with this condition.11

Conclusions

An incidental bizarre, abnormal, anomalous radiographic pattern has been described to help radiology technicians and dental assistant personnel broaden the inventory in their "radiographic pattern recognition" mental libraries. Providing this group of healthcare personnel with an understanding of the terminology, etiology, clinical findings, and prognosis associated with the unusual radiographic pattern observed in this case ensures that referral for further interpretation can be performed more proficiently.

References

- Stedman's Concise Medical Dictionary for the Health Professions, 3rd ed. New York: Williams & Wilkins, 1997: 2, 51, 428.

- J Dent Radiogr Photogr series. Rochester, NY: Eastman Kodak Co., 1927-1985; vols.1-57.

- Kung JC, Chaung FH, Hsu KJ, Shih YL, Chen CM, Huang IY. Extensive subcutaneous emphysema after extraction of a mandibular third molar: A case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2009; 25: 562-566.

- Azhena MR, Yamaji MAK, Avelar RL, Resende de Freitas QE, Filho JRL, Neto PJ. Retropharyngeal and cervicofacial subcutaneous emphysema after maxillofacial trauma. Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011; 15:245-249.

- Smatt Y, Browaeys H, Genay A, Raoul G, Ferri J. Iatrogenic pneumomediastinum and facial emphysema after endodontic treatment. Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surg 2004; 42:160-162.

- Patel N, Lazow SK, Berger JB. Cervicofacial subcutaneous emphysema: Case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010; 68:1976-1982.

- Hupp J, Ellis E, Tucker MR. Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 5th ed. New York: Mosby Elsevier, 2008: Chapter 16.

- Liebgott BL. The Anatomical Basis of Dentistry, 3rd ed. New York: Mosby Elsevier, 2011: Chapter 11:482.

- Hulsmann M, Hahn W. Complications during root canal irrigational subcutaneous emphysema: Case report.Int Endod J 2000; 33:186-18.

- Neville BW, et al (eds): Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 2002: Chapter 8:323-324.

- Rickls NH, Joshi BA. Death from air embolism during root canal therapy. J Am Dent Assoc 1963; 67:399-404.