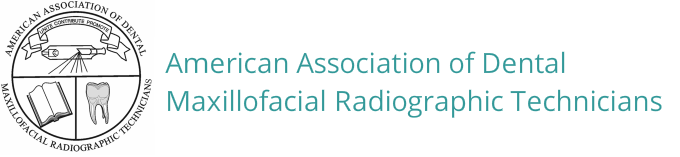

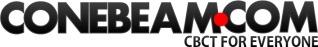

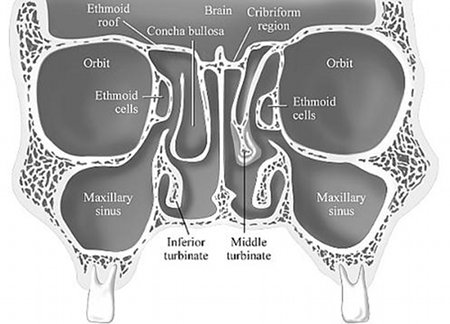

Figure 2, 3: Maxillary sinuses are located bilaterally below the orbit. Images from Google internet search.

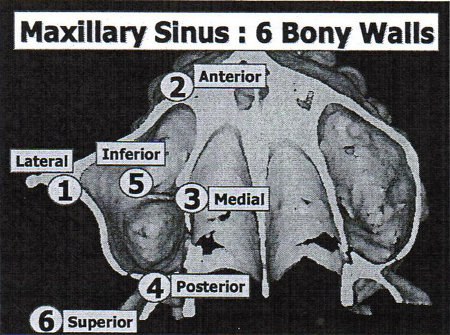

Figure 4: Maxillary Sinus has six bony walls (Lateral, anterior, medial, posterior, inferior, superior walls). Image from RR. Resnik Lecture on Radiographic Interpretation of the Maxillary Sinus, Misch International Implant Institute CE Course, March 2010.

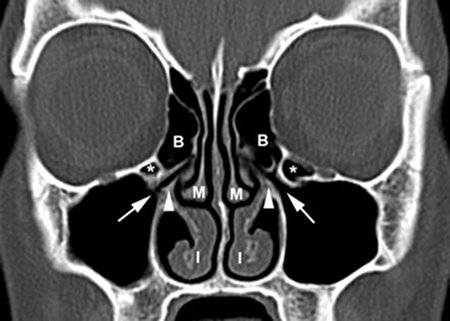

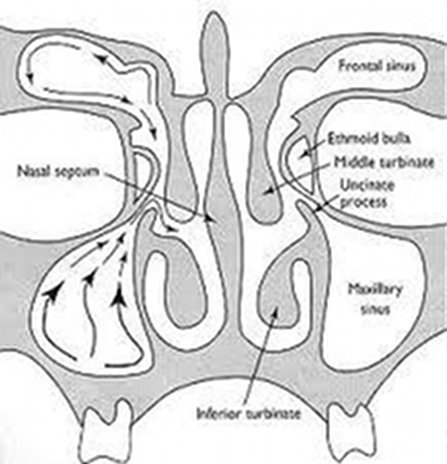

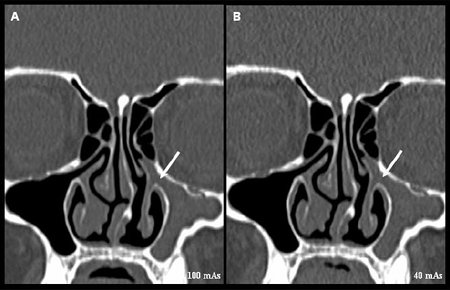

The osteomeatal complex is the anatomical region where the frontal and maxillary sinus meets and open to the nasal cavity. Included in this complex is the ostium, which is the pathway that allows sinus secretions to drain out from the maxillary sinus to the nasal cavity (Figure 5).

The osteomeatal complex is the anatomical region where the frontal and maxillary sinus meets and open to the nasal cavity. Included in this complex is the ostium, which is the pathway that allows sinus secretions to drain out from the maxillary sinus to the nasal cavity (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Arrows depict an open ostium bilaterally. From American Journal of Roentgenology, Figure 1. December 2007 vol. 189 no. 6 Supplement S35-S45

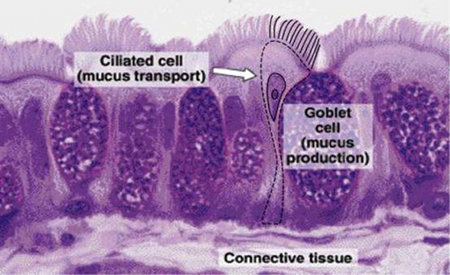

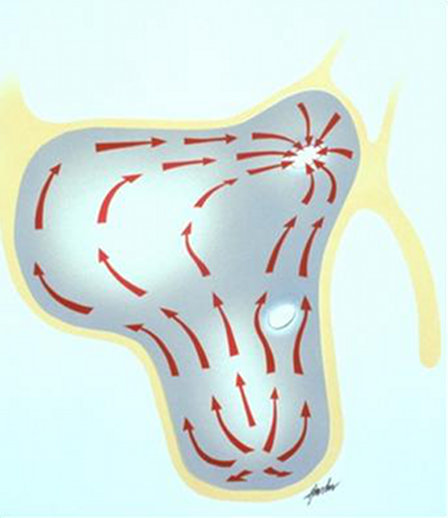

At a microscopic level, pseudostratified columnar epithelial cells line the maxillary sinus (Figure 6). These cells are ciliated, brush-like projections which continually sweep in a beating motion and clear mucus (along with potential toxin particles) from the sinus chamber through the ostium and into the nasal cavity (Figures 7, 8).

At a microscopic level, pseudostratified columnar epithelial cells line the maxillary sinus (Figure 6). These cells are ciliated, brush-like projections which continually sweep in a beating motion and clear mucus (along with potential toxin particles) from the sinus chamber through the ostium and into the nasal cavity (Figures 7, 8).

Figure 6: Micrograph depicting the main components of the respiratory epithelium, ciliated and goblet cells. The nuclei of basal cells are present also. Taken from Junqueira and Carneiro, Basic Histology, a text and atlas, p. 350, Figure 17-2.

Figure 7: Pathway of sinus drainage through the ostium. Image from Google internet search.

Figure 8: Pathway of sinus drainage inside the maxillary sinus. Ciliated cells continually sweep mucous towards the ostium.

When the maxillary sinus is healthy, there is a continual cycle of mucus production, clearance by cilia, and drainage through the ostium. Serous and goblet cells in the sinus membrane produce up to 1L of mucus each day. Bacterial or viral infections, pollution, allergens, and smoking can negatively affect the action of cilia, reducing their propulsion and sweeping efficiency.

The functioning of this mucociliary transport system relies heavily on an adequate supply of oxygen passing through the ostium into the maxillary sinus cavity. When the ostium is open, the maxillary sinus environment is aerobic and normal ciliary function is maintained. When the ostium is closed, the maxillary sinus environment can become anaerobic, resulting in a change in bacterial flora that favors the colonization and growth of anaerobic bacteria, which leads to maxillary sinusitis (also known as acute maxillary sinusitis or acute maxillary rhinosinusitis). Symptoms of acute maxillary sinusitis can be debilitating to the patient and may include fever, severe headache, toothache, and pressure pain in the cheek. Treatment may include the use of antibiotics, saline nasal rinses, or nasal steroids. In some cases, multiple systemic antibiotics may be used without successful resolution of the sinus infection. In patients who are refractory to more than one antibiotic treatment, a potential serious complication is fungal infection which can spread through the adjacent sinuses to the brain and account for 5-10% of brain abscesses each year.

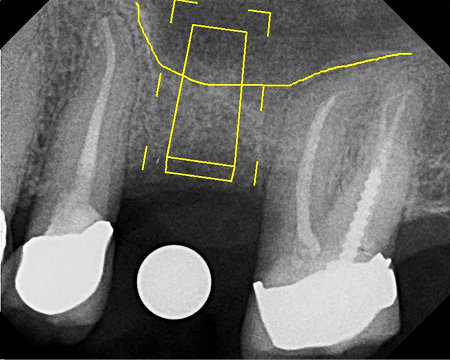

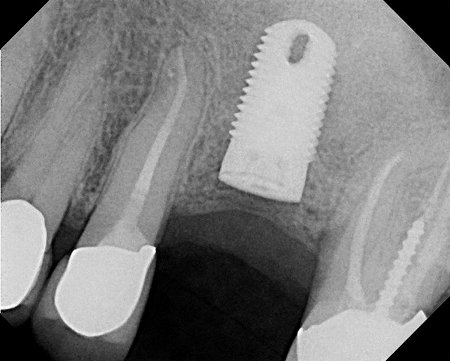

Sinus augmentation requires the separation of the sinus membrane from the bone wall and the placement of bone graft beneath the membrane. Often times the membrane will need to be elevated 15-20mm in height to add sufficient bone graft material for placement of a 13mm length dental implant (Figure 9).

When the maxillary sinus is healthy, there is a continual cycle of mucus production, clearance by cilia, and drainage through the ostium. Serous and goblet cells in the sinus membrane produce up to 1L of mucus each day. Bacterial or viral infections, pollution, allergens, and smoking can negatively affect the action of cilia, reducing their propulsion and sweeping efficiency.

The functioning of this mucociliary transport system relies heavily on an adequate supply of oxygen passing through the ostium into the maxillary sinus cavity. When the ostium is open, the maxillary sinus environment is aerobic and normal ciliary function is maintained. When the ostium is closed, the maxillary sinus environment can become anaerobic, resulting in a change in bacterial flora that favors the colonization and growth of anaerobic bacteria, which leads to maxillary sinusitis (also known as acute maxillary sinusitis or acute maxillary rhinosinusitis). Symptoms of acute maxillary sinusitis can be debilitating to the patient and may include fever, severe headache, toothache, and pressure pain in the cheek. Treatment may include the use of antibiotics, saline nasal rinses, or nasal steroids. In some cases, multiple systemic antibiotics may be used without successful resolution of the sinus infection. In patients who are refractory to more than one antibiotic treatment, a potential serious complication is fungal infection which can spread through the adjacent sinuses to the brain and account for 5-10% of brain abscesses each year.

Sinus augmentation requires the separation of the sinus membrane from the bone wall and the placement of bone graft beneath the membrane. Often times the membrane will need to be elevated 15-20mm in height to add sufficient bone graft material for placement of a 13mm length dental implant (Figure 9).

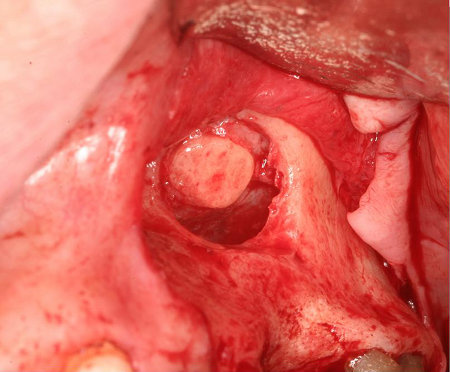

Figure 9: Sinus Augmentation Implant Case (Chuck Leavitt, Gil Granucci, Carol Hickerson)

It is necessary to ensure that the maxillary sinus cavity is healthy prior to performing the sinus augmentation procedure. In a healthy maxillary sinus, there is air (and absence of fluid) in the sinus chamber and the ostium is patent. To properly visualize these structures, 2-dimensional radiographic imaging is inadequate.

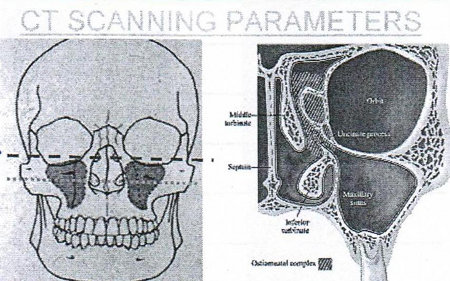

Radiographic evaluation of the maxillary sinus is best done with 3-dimensional cone beam CT technology. CT scanning parameters must be set so the superior border of the scan is just above inferior aspect of the orbital rim so the ostium can be viewed (Figure 10).

It is necessary to ensure that the maxillary sinus cavity is healthy prior to performing the sinus augmentation procedure. In a healthy maxillary sinus, there is air (and absence of fluid) in the sinus chamber and the ostium is patent. To properly visualize these structures, 2-dimensional radiographic imaging is inadequate.

Radiographic evaluation of the maxillary sinus is best done with 3-dimensional cone beam CT technology. CT scanning parameters must be set so the superior border of the scan is just above inferior aspect of the orbital rim so the ostium can be viewed (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Dashed line reveals superior border of scan to capture ostium. From RR. Resnik Lecture on Radiographic Interpretation of the Maxillary Sinus, Misch International Implant Institute CE Course, March 2010.

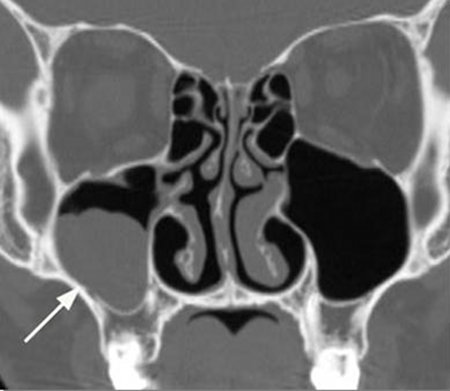

If the ostium is opaque and therefore obstructed, sinus grafting should be delayed until the sinus pathology is addressed, and referral to the patient's physician or ENT is necessary. If a sinus augmentation is done with an obstructed ostium, moving the sinus membrane with a sinus lift could further alter ciliary function, resulting in acute sinusitis. Most often other pathology will be evident with an occluded ostium, such as build up of fluid in the sinus chamber (Figure 11). When there is fluid or an inflamed sinus membrane with chronic sinusitis or a sinus cyst, there will be varying degrees of gray in the sinus chamber (Figure 12).

If the ostium is opaque and therefore obstructed, sinus grafting should be delayed until the sinus pathology is addressed, and referral to the patient's physician or ENT is necessary. If a sinus augmentation is done with an obstructed ostium, moving the sinus membrane with a sinus lift could further alter ciliary function, resulting in acute sinusitis. Most often other pathology will be evident with an occluded ostium, such as build up of fluid in the sinus chamber (Figure 11). When there is fluid or an inflamed sinus membrane with chronic sinusitis or a sinus cyst, there will be varying degrees of gray in the sinus chamber (Figure 12).

Figure 11: Right maxillary sinus is clear with a patent ostium while the left sinus shows fluid in the sinus chamber and an obstructed ostium (arrow). From Biomedical Imaging and Intervention Journal 2009.

Figure 12: Coronal view. Right maxillary sinus mucous retention cyst. Image from Google internet search.

For surgeons performing maxillary sinus grafting, a reformatted transaxial CT scan is needed as a "clearance" that the sinus is healthy prior to performing the surgical procedure. In my practice, I always have this scan taken with a radiographic guide to most accurately assess bone dimension at the exact position of ideal implant placement. The scan imaging software can be used to scroll through the coronal slices to view the ostium and the sinus chamber. Taking this step to evaluate a CBCT scan with the proper scan parameters will ensure the sinus is healthy prior to performing the procedure, and will reduce the potential for a complication such as maxillary sinus infection.

For surgeons performing maxillary sinus grafting, a reformatted transaxial CT scan is needed as a "clearance" that the sinus is healthy prior to performing the surgical procedure. In my practice, I always have this scan taken with a radiographic guide to most accurately assess bone dimension at the exact position of ideal implant placement. The scan imaging software can be used to scroll through the coronal slices to view the ostium and the sinus chamber. Taking this step to evaluate a CBCT scan with the proper scan parameters will ensure the sinus is healthy prior to performing the procedure, and will reduce the potential for a complication such as maxillary sinus infection.

references

- Tatum OH: Lecture presented at Alabama Implant Study Group, Birmingham, AL, 1977.

- Garg AK: Augmentation Grafting of the Maxillary Sinus for Placement of Dental Implants. In Garg AK: Bone Biology, Harvesting, Grafting for Dental Implants: Rationale and Clinical Applications. Quintessence Publishing Co, Hanover Park, IL 2004.

- Misch CE, Resnik, RR, Misch-Dietsh, F: Maxillary Sinus Anatomy, Pathology, and Graft Surgery. In Contemporary Implant Dentistry 3rd Ed., St. Louis, Mosby Elsevier, 2008