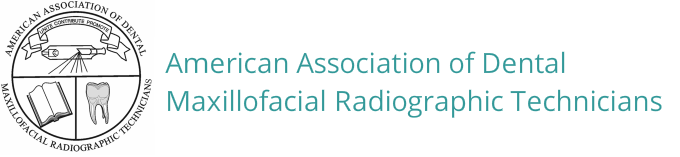

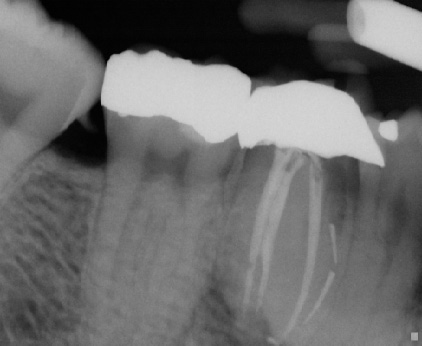

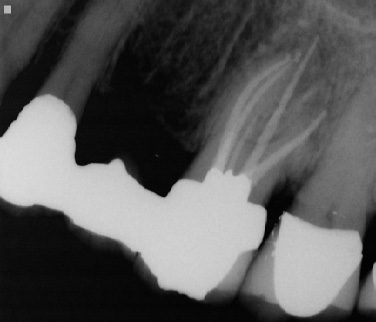

Intra-operatively, radiographs are used to determine the length of the canals and the gutta percha cone fit to the apices. These films are taken with the file or cone placed in the canal(s) (Fig. 2 a-b). However, with the advent of the Electronic Apex Locator, the need to take a length film has been reduced significantly. Most of the time one can rely on accurate measurements of the true biological apex of the canal using the apex locator. Nevertheless, there are times such as in the case of a metal crown, bleeding, or a long standing periapical abscess, that the apex locator fails to provide an accurate measurement thereby requiring a radiograph to determine length.

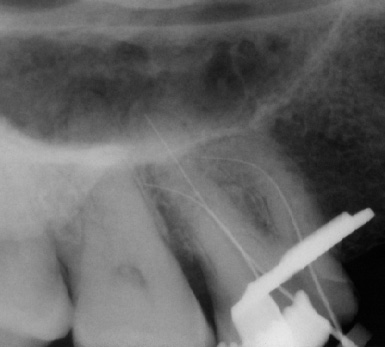

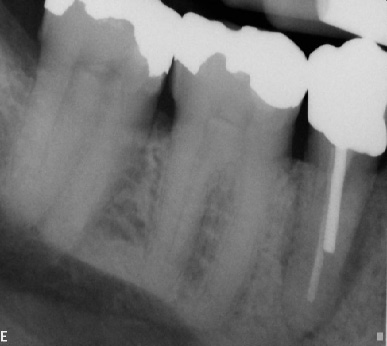

Post-operatively, radiographs are used to check the quality of the obturation (fill) and are used as a baseline reference for the recall appointment. For example if a periapical lesion was present preoperatively (Fig. 3), the size and location would be recorded radiographically and could be checked during recall visits to ensure extent of healing and resolution of the lesion. The radiographs may also show if there is gutta-purcha or sealer extruded beyond the apex and the patient can be informed of possible post-operative sensitivity.

Recall visits are extremely important in endodontics as it is often through the radiographic healing that we measure success of the treatment. Although the patient may not present with symptoms at the time of recall, the radiographs may reveal a periapical lesion remaining. In those cases the endodontist may have to choose retreatment or surgery (Fig. 5).

The SLOB Rule

The SLOB rule is one of the most widely used radiographic concept in endodontics. On periapical radiographs, roots are often superimposed upon one another and require separation for proper identification. The SLOB rule is an acronym for Same Lingual Opposite Buccal. The premise is that one radiograph is taken straight on at a 90 degree angle to the tooth and a second radiograph is taken with the tubehead shifted either mesially or distally. The rule simply states that the object imaged will move in the same direction as the tubehead is moved if it is located on the lingual (Same Lingual). Conversely, the object being imaged will move opposite the tubehead movement if it is located on the buccal (Opposite Buccal). An example of this would be a palatal root, which is on the lingual side of a maxillary molar, will move mesially on the image if the tubehead moves mesially (Same Lingual).

During root canal treatment the endodontist may need to separate the canals to visualize lengths and anatomy. Another important application of this rule would be in the case of a separated instrument. It is quintessential to know which canal the instrument is in for both clinical and documentation purposes. Sometimes just changing the angulation of the beam can aid in identifying factors that are not visible on the straight (perpendicular) shot. Those findings can include root fractures, additional roots or canals etc. The key to this technique is to remember which direction the tubehead was angulated on the second radiograph since the image receptor may not be placed in the exact location of the first image (Fig. 6 a-b & 7 a-b). Labeling the radiographs can help alleviate any doubt and will help in archiving the images. Images can be simply labeled as "straight" for the first and "mesial" or "distal" for the off-angled image. If using film, it is easy to label the images by just using a 2 hole mount and a wax crayon or pencil. Most digital images can be labeled by adding a text box or using the tools available in the software to add notes. Training the staff to use the same system also aids in consistency of the technique and proper archiving of the images.

The SLOB rule is one of the most widely used radiographic concept in endodontics. On periapical radiographs, roots are often superimposed upon one another and require separation for proper identification. The SLOB rule is an acronym for Same Lingual Opposite Buccal. The premise is that one radiograph is taken straight on at a 90 degree angle to the tooth and a second radiograph is taken with the tubehead shifted either mesially or distally. The rule simply states that the object imaged will move in the same direction as the tubehead is moved if it is located on the lingual (Same Lingual). Conversely, the object being imaged will move opposite the tubehead movement if it is located on the buccal (Opposite Buccal). An example of this would be a palatal root, which is on the lingual side of a maxillary molar, will move mesially on the image if the tubehead moves mesially (Same Lingual).

During root canal treatment the endodontist may need to separate the canals to visualize lengths and anatomy. Another important application of this rule would be in the case of a separated instrument. It is quintessential to know which canal the instrument is in for both clinical and documentation purposes. Sometimes just changing the angulation of the beam can aid in identifying factors that are not visible on the straight (perpendicular) shot. Those findings can include root fractures, additional roots or canals etc. The key to this technique is to remember which direction the tubehead was angulated on the second radiograph since the image receptor may not be placed in the exact location of the first image (Fig. 6 a-b & 7 a-b). Labeling the radiographs can help alleviate any doubt and will help in archiving the images. Images can be simply labeled as "straight" for the first and "mesial" or "distal" for the off-angled image. If using film, it is easy to label the images by just using a 2 hole mount and a wax crayon or pencil. Most digital images can be labeled by adding a text box or using the tools available in the software to add notes. Training the staff to use the same system also aids in consistency of the technique and proper archiving of the images.

|

|

Clinical Case

Patient presented for root canal treatment on tooth #14. The canals were extremely calcified and after three visits we were able to complete the case (Fig. 9 a-b). Convinced that we had provided the best possible treatment for the patient and were able to find all of the canals the patient was discharged only to return three months later with recurrent pain. Upon careful examination she expressed tenderness upon biting and palpation of the mesiobuccal root. A distal angle radiograph revealed a wide mesiobuccal root indicating a possible additional canal in that root (Fig. 10). The case was accessed and the canal was found and treated (Fig. 11)

Patient presented for root canal treatment on tooth #14. The canals were extremely calcified and after three visits we were able to complete the case (Fig. 9 a-b). Convinced that we had provided the best possible treatment for the patient and were able to find all of the canals the patient was discharged only to return three months later with recurrent pain. Upon careful examination she expressed tenderness upon biting and palpation of the mesiobuccal root. A distal angle radiograph revealed a wide mesiobuccal root indicating a possible additional canal in that root (Fig. 10). The case was accessed and the canal was found and treated (Fig. 11)

Periapical radiographs still remain the imaging of choice for the endodontist. The convenience of digital radiography for intra-operative periapical radiographs make it an ideal technique to achieve the diagnostic goals stated previously. Although endodontics has used these types of images in the past and present, the future may lend to new techniques. With the technological advancements in Oral Radiology many new imaging techniques are emerging that may supplement the basic techniques currently being used. Imaging such as Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT), which scans patients at high resolution, may aid in pre and post operative imaging. Diagnosing cracked teeth, preparing for apical surgery or searching for missed canals may also be possible using this new treatment modality. For intraoperative procedures however, the digital periapical image remains a great asset.